- Home

- Olga Slavnikova

2017 Page 2

2017 Read online

Page 2

“You can call me Vanya. Then we’ll rhyme,” Krylov proposed.

“Tanya-Vanya? Kindergarten stuff,” the woman shrugged, frowning at the pizza plunked down in front of her on the table by the long-legged young waitress in red shorts. “Why don’t I try to guess your profession instead?”

“College history teacher!” Krylov reported so quickly and loudly that now all the waitresses, who depicted a sports team—the current fashion—looked at the couple at the far table, and the fat, watchful manager with tomato-red lips stuck his head out of the storeroom. “Another pizza with mushrooms for each of us,” Krylov shouted out, and that calmed them down right away. The manager dragged himself into his office, and the long-legged waitress passed the hard ball on a string with the café’s logo to her colleague and stuck two plates with the thick premade circles into the microwave.

“You’re going to eat those yourself,” said “Tanya,” smiling and frowning. “Do you want to know my profession?”

“Not really. I’d rather you told me whether you’re married.”

“Yes. So, you mean my profession doesn’t matter?”

“Hardly at all. Especially for a woman.”

“Are you waiting for me to get mad? Don’t hold your breath.”

“Usually ladies object to comments like that. Especially the ones who function as furniture at work.”

“I function at work as a gray mouse. I graduated from the university, and I work in my specialty, which I acquired in a four-month course. Just unlucky, I guess.”

“There’s lots of that going around now. The television is the friend of the unemployed.”

“You’re not one of those political activists, are you? They’re crazy and they hand you completely dopey leaflets on the street.”

“Do I look crazy?”

“Forgive me, but you look a little like an intellectual.”

“No, word of honor, I’m not crazy.”

What Krylov could never figure out later was the unremarked disappearance of the sweater package, which never was passed on to Anfilogov. When he was walking behind the stranger across the station plaza he had definitely had the package, which kept thudding against his legs; later, in the chilly park, where it was June in the sun but the solid shadow had a May chill to it, Krylov was about to suggest to the shivering woman that she at least throw the sweater over her shoulders—but at the time “Tanya” had the package, a fact “Ivan” was embarrassed to point out. Later they wandered down steep paths, which would occasionally turn into concrete steps sealed with rough plaster; once they came across a booming band shell, where well-dressed old women were waltzing, dragging their puffy legs across the boards, to a hoarse accordion, and a little farther on they were held up by a packed group of young people with shaved heads clapping steadily and handing out free posters. Farther on, in untended weeds more characteristic of a public outhouse, they discovered a small movie house made appealing by the cheapness of its tickets and the touching old-fashioned quality of its sturdy columns, over which the white plaster seal of the USSR reminded them of Caesar’s bald pate. However, the next few shows were for kids—an old cartoon about the Star Pirate—and they both realized it would be simply unbearable to wait four hours for the old comedy.

“We are both grownups, after all,” said “Tanya” in an angry, slightly dejected voice.

By then the package was gone for good—maybe left in the rickety taxi where they’d kissed and gasped, as if the air were being pumped out of the cab, and they kept popping up in the rearview mirror, which the narrow-shouldered, slicked-down driver kept righting, as if pouring off its contents. Anfilogov’s apartment, where Krylov wasn’t supposed to feed the unfinicky, nickeled fish for two days, greeted them with the daytime gloom of its only room, which was stacked to the ceiling with thousands of dark, inosculating volumes; from the outside, the other side of the tightly closed curtains, which were full of hot sunny color, a flock of pigeons was clawing hard at the metal. The narrow professorial cot was unmade.

“For the first and last time,” “Tanya” whispered hoarsely, and “Ivan” whispered something into her hot, bitterish ear, too, tugging at the zipper on her dress, which he couldn’t get unstuck.

After undressing each other, they tromped around in the checked scuffs they’d happened to pick out by the front door—one clumsy pair for the two of them. When “Tanya” pulled her multilayered gauze over her head, her glasses slipped down and got tangled up, and they had to be picked out of her dress, like a butterfly from a big floppy net. Despite her sham proficiency, she was thoroughly spooked, not having been touched in a very long time. Her nipples were big and soft, like overripe plums, and on her narrow, slightly sagging tummy there was a scar that looked like a thread of cooked noodles. On her skin, which resisted “Ivan’s” lips with a tiny puckered wave, he kept encountering spots that burned as if they’d been rubbed with a medicinal ointment, as if she were really not very well. The moment “Ivan” succeeded in bringing her to her first weak climax, “Tanya” let out a muffled cough, and her temples became swollen and damp. Later, when “Ivan,” after her whisper-short time in the shower, went to rinse off, too, he saw that the mirror hadn’t even fogged up from her bathing.

They fell asleep instantly, completely forgetting when they dropped off; the sagging hammock of the professor’s cot was barely big enough. Later they admitted to each other that the first time they hadn’t felt anything special; it was sleeping spoon-fashion that had evidently brought about the decisive change. They lay there chastely and closely, like twins in their mother’s womb, and truly did start looking more and more alike. The room’s summertime semi-dark, without the negative intervention of a lamp at the transition from sun to night, was amazingly pure. All the dishes in the room were empty but seemed full; the dull, congealed crystal of the cut glass on the desk, the size of a half-liter tin, seemed to be reading the newspaper under it through a magnifying glass. The decorative fish no longer saw the glass wall of the aquarium as a solid barrier and swam freely about the room, their tiny maws nibbled at the offal of scattered clothing, and their insides looked like dark tangles, which would occasionally isolate a fat thread hanging in the air. The blanket had slipped off; almost simultaneously, struggling to retain the last grains of their winding, all the clocks in the house went off. In their sleep, the quotation marks fell away from their invented names; at half past five, when the streets deepened and a band of sunlight passed over the roofs, like a gilt fillet around a glass’s rim (while in the grubby train carrying him northward, the professor suddenly sat up on his shifted mattress and pressed his hands against his angular face), they both surfaced from their dreams as other people and felt that this time was by no means the last.

They began meeting but in secret, because according to the normal logic of things, what had happened to them was impossible. Why him? Why her? They were surrounded by hundreds, thousands of people to whom nothing like this ever happened.

Krylov was probably not at his best. His eyes, which were too beautiful for a man, as his ex-wife used to say, envying their cornflower blue color and their wonderfully curled, feathery-thick eyelashes, now pulsed red, bloodshot, and his rusty stubble soon made his chin look like yesterday’s schnitzel, no matter how often Ivan shaved. His steady clients—half of them respectable, elderly Jews, self-described failures, and half of them wiry rock hounds who smelled of the forest—were worried that the maestro was unwell, which was how they explained the condition of this man who had placed himself in the hands of fate.

Tanya and Ivan had apparently been stricken in earnest by that ancient and virulent disease that no medicine in the world has ever vanquished. The hostile environment couldn’t kill the virus off straightaway, and now they kept reinfecting each other with each kiss and the nomadic love they made in rooms rented by the day in tourist hotels. The vaccines life had inoculated them with didn’t help, either. All those lonely women of a certain type (a tic over one eyebrow, a dr

amatic shawl) with whom Krylov had readily shacked up for half a year or a couple of weeks at a time had not given him any immunity. As for his relations with his ex-wife, whom Krylov had managed to divorce but not leave, they lent his life an unbearable sadness and had never inspired the surges of soundless inner music Krylov was dancing to as he moved through the blurry world between home and workshop.

Their illness nonetheless required protection, a bell jar. A propitious confluence of circumstances—the encounter at the train station and immediate departure of Anfilogov (whose apartment was immediately snapped up by his student niece, a tenacious girl with a luminescent manicure and swivel hips that Krylov barely managed to dodge)—had given them a chance to make a clean break with real life, where they were both ordinary people. Neither had any doubt that they had only one, not very sound basis for their reality, and if they started digging around too casually they would discover common acquaintances and events that pertained to them both. In no case were they to look for each other in the real world because that would mean coming at it from the wrong side. Both knew that there was only one way into the place where they exchanged tenderness, moisture, and animal warmth (and something on top of that, something transmitted not directly but as if via a satellite hovering constantly overhead), and this was their big secret.

They knew almost nothing about each other—and guarded against knowing. At the very beginning, Tanya let slip that she worked as a bookkeeper in a small publishing house. Ivan found this touching and unusual for some reason, although the owner of the gemcutting workshop where he worked (he also owned a couple of stores which, in addition to his cheap legal jewelry, were stacked to the ceiling with second-hand clothes that stank of disinfectant) had bookkeepers as well: two middle-aged women with boyish bangs and hair chopped off at the nape. Krylov swore at these ladies because when they filled the kettle in the one and only shared bathroom they detached the hose that fed the workbenches and let the water spill out on the floor, and as a result the grinding wheels would heat up and a puddle would collect next to the hose, flooding the far corner where the tile was broken. Many times Krylov had asked his boss to put those messy ladies in one of his stores, nearer the dresses, but the tubby little man, who was overgrown with musty wool and who cherished his joyless tranquility, would merely point wordlessly to the catacombs of goods that occupied every storeroom and that looked like circus costumes for trained apes.

Now, each time he saw the bookkeepers, Krylov thought of Tanya and gave them a dreamy, diffuse smile—and in response he suddenly began receiving homemade pirozhki on fine china with a crown monogram from some restaurant he’d never heard of. In a scary way, both ladies instantly became prettier, and their downcast eyes, framed in thick silver, reminded him of champagne corks. He now would find the unfortunate hose mostly reattached and spritzing the mirror, but his materials no longer suffered from dry abrasive.

Too much information about each other could have affected their reality, made it too human. Krylov had no intention of loving his sundry neighbors through Tanya. The only thing that interested Krylov (he couldn’t help it) was Tanya’s husband, who had first been mentioned in the red plastic café and whom Ivan’s efforts had transformed into an exaggerated, nearly relentless figure. From certain oblique but unquestionable signs Krylov realized that Tanya was not seeing anyone else. Each time she freed herself from her baggy skirts and peasant tops with the knotty lace (it didn’t take long for Ivan to know all her summer things and the minor quirks of their harassing fasteners), she would be slightly stiff—stale, in a way. To help her catch up to today, he had to literally wake up her long body and massage the blood pooled under her cold skin, whose goose bumps reminded him of sleet. A lifetime of experience, however, suggested to Krylov that there are marriages without physical intimacy, especially those fouled in a complicated net of moral obligations, having become a nearly indissoluble symbiosis.

Feigning indifference as he steered the conversation to the sensitive topic, he tried to assemble an avatar of his invisible enemy. From Tanya’s reluctant answers (her eyes always dimmed then, and her glasses glinted angrily), he compiled a positive, but grim image utterly devoid of life. This man, had he existed in reality, would have had to be kept in a box and run off the electric power grid. Tanya stuck to her story about her marital situation, though, and turned to stone the moment Ivan tried to make her admit her lie. If they had this difficult conversation in bed (and Ivan, tactless and impulsive as only a truly ill man can be, summoned up that specter even when they were all alone), Tanya would turn abruptly to the wall and immediately find something interesting in the paper herbarium of the neutral wallpaper, allowing Ivan to study her untanned shoulder blades just as steadily. Temporarily mollified, Ivan would beg her forgiveness, kiss the Latinate “N” on her palms, and catch her chilly smile with his lips as if it were a stream of drinking water.

All Ivan’s insistence led to was the husband, defended from his attacks with rash obstinacy, becoming more and more ideal. As he lost human authenticity, he gained more and more positive qualities, preeminent among which was a maniacal domesticity. Ivan was indignant at the thought that at the very moment he was holding Tanya that indomitable rogue was having a grand time vacuuming the rugs or chopping boiled beets for salad. He saw that no matter how sincere her impulses for him, through some logical twist of mind he didn’t get, Tanya was faithful to her mechanical doll.

Ivan was even more perturbed by the fact that he himself was unfaithful to Tanya and didn’t know what to do about that. She, meanwhile, did not ask questions. The only thing that reassured him was that the husband, if he did exist, was obviously not a rich man. Testimony to this was not only Tanya’s modest wardrobe but also her few pieces of jewelry, dark and small, like thorny weeds with dingy seeds. In them Ivan’s unerring specialist’s eye determined imitation diamonds made of cubic zirconium and crystal.

“Could you go with me somewhere far away?” Ivan once asked, his arm around Tanya, near an iron parapet behind which an invisible nocturnal pond squelched like a hot water bottle.

“I could fly to the moon with you.”

“But there’s no air on the moon.”

“Are you sure we’re breathing air right now?”

Ivan took a deep breath. The smells of the sludgy bottom rose from the water; the small white inflorescences beside it, swarming in the darkness, exuded a faint vanilla scent; coming from somewhere was the smell of grilled meat, music, and loud conversation.

“It’s a quote from an old movie,” Tanya said conciliatorily, huddling in her cotton print against the damp breeze.

Nonetheless she had expressed what they were afraid to say. Everything around them was unreal. The two cut-crystal glasses that were the Economic Center glowed dully, and the moon shone overhead like an elevator button.

“Can we go any farther away than we already are?” Tanya said softly, and Krylov had nothing to say in reply.

Krylov knew that a war over a woman, no matter how little she valued material goods, meant economic war. Fortunately, poor Tanya lacked that multilayered polish of opulence that turns a person into his own depiction and brings his everyday appearance maximally close to the photographs in the glossy rags that feed the public their weekly dose of society gossip. These rags, actually, pursued the couple from hotel to hotel, lying like frayed butterflies around their rooms—and sometimes Ivan would pull a flimsy drawer out of a piece of furniture and suddenly come across a photo of his former spouse beaming her killer smile, responding with this standard flash to the camera’s attacking flashes.

Tamara liked to have her picture taken in her emerald necklace, whose split stones Krylov had only recently repaired. At the thought of how many times he had fastened that necklace on Tamara’s bent neck, Krylov felt his heart ache, slowly. He realized (in the meagerly lit hotel pencil box, under the barely warm shower, which encircled his body with a limp rope of water) that the secret he and Tanya were shielding from the wo

rld left Tamara with her position as the principal woman in Krylov’s life. All his other occasional girlfriends—always beauties with aplomb, always with some bizarre defect, like a big navel resembling a candle end, or toxic armpits—fell under her chilly tutelage and, unable to withstand the comparison with her, quickly dropped Krylov. Sometimes Tamara seemed to be picking up on signs of life in him—the very life that was slipping away from this radically rejuvenated woman who had everything, but was connected with this “everything” solely by right of ownership. A thin layer of emptiness had formed between Tamara and reality, and it clothed her like a beautiful dress. Krylov remained for Tamara the last battlefield where she might encounter women like herself, who would make her feel more alive than any man could.

Tanya was a through-the-looking-glass creature. Krylov couldn’t imagine bringing her to Tamara’s suburban home, where at any time of day or night you couldn’t see anyone in the lit windows, but in the unlit rooms you might bump into anyone at all, from a youthful poet curled up asleep to a State Duma deputy attempting to move a bottle of cognac by the power of the firm stare under his swollen brow. In this world, Tanya was by definition absent. Therefore, the world of which Tamara was the legitimate center did not change a bit with Tanya’s appearance.

The expedition’s result was supposed to resolve this tug-of-war of many years between Krylov and Tamara over who could get along without the other first. The people around them thought they’d split up over the difference in their success and social status. But proud Tamara would never have stooped to a base comparison of incomes. Unlike many women in business, Tamara didn’t even try to set her husband up as an executive—Director of the Analytical Center for the Study of the Doughnut Hole, or Chairman of the Regional Committee for the Defense of Domestic Insect Rights—such as made serious people smile quietly but justified wearing a brand-name tie. She had given her husband every opportunity to be himself, that is, in society’s understanding, a simple craftsman. She had guessed that Krylov’s feel for stone had made him a representative of the forces secretly behind the gem-filled Riphean lands, that is, a representative of a power in some sense more legitimate than a governor’s.

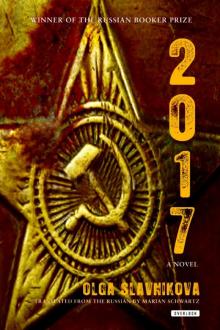

2017

2017