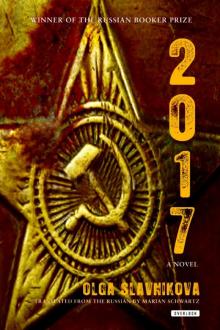

2017 Read online

Copyright

This edition first published in hardcover in the United States in 2010 by

Overlook Duckworth, Peter Mayer Publishers, Inc.

New York • London

NEW YORK:

141 Wooster Street

New York, NY 10012

LONDON:

90-93 Cowcross Street

London EC1M 6BF

[email protected]

www.ducknet.co.uk

Copyright © 2010 by Olga Slavnikova

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system now known or to be invented, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who wishes to quote brief passages in connection with a review written for inclusion in a magazine, newspaper, or broadcast.

ISBN 978-1-46830-290-5

Contents

Copyright

Translator’s Acknowledgments

Part One

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Part Two

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Part Three

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Part Four

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Part Five

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Part Six

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Part Seven

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Part Eight

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Part Nine

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Part Ten

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

TRANSLATOR’S ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Many people and institutions have been instrumental in bringing this translation to the American reading public, for which I want to express my deep gratitude.

Natasha Perova, the pioneering editor of Glas: New Russian Writing, introduced me to Olga Slavnikova’s work and published an excerpt from a previous version of the novel in 2003, in a volume entitled Nine of Russia’s Foremost Women Writers.

The National Endowment for the Arts provided a major grant in support of this translation. Without it, I would never have been able to take the necessary time to complete the novel.

David Leavitt, editor of the fine literary journal Subtropics, published an excerpt from this translation in 2007 and has been a champion of both Slavnikova’s work and mine.

As he has in the past, my dear friend and colleague R. Michael Conner shared his long experience and invaluable counsel on geological terminology.

My agent, Peter Sawyer, of the Fifi Oscard Agency, and before him Fifi herself, have been unfailing supporters of this translator’s sometimes obscure endeavors.

Most of all, I want to thank the author for writing such an amazingly fresh and exciting book about Russia..

Part One

1

ON JUNE 7, 2017, KRYLOV WAS SUPPOSED TO BE AT THE TRAIN station at seven thirty. He had no idea how he’d overslept, and now he was loping between winding puddles that reminded him of Matisse dancers in extended poses who had confused right and left. Krylov’s arms were wrapped around a camel’s hair sweater crammed into a plastic bag. He had to give the sweater back to Professor Anfilogov, to replace one that had been irreparably damaged by moths: in the north, which it was going to take the expedition three weeks to reach, spring was only just coming into its own, and under the drunken spruce trees, in the shelter of their broad black shawls, the stony snow, strewn with needles, was still white. As Krylov raced across the plaza in front of the station, his sneakers smeared the oozy mess that had fallen from the bird cherry trees. He glanced at the gray tower with the square clock, where the arrow, like a blind man’s cane, had ticked and just missed the Roman IV, and realized he would make it—with time to spare.

Krylov was so much lighter than the rest of the train station crowd, which was sorely weighed down by the baggage it was dragging, he was practically skimming past a pile of oilcloth valises when his attention was captured by a gossamer-wrapped woman. The stranger shone through her thin, gauzy dress and was silhouetted in a sun cocoon, like a shadow on a dusty windowpane. Scurrying between Krylov and the stranger were a great many people wholly absorbed in their own baggage. No one saw anything around them but the arrivals and departures board, half erased by the sun, where, at irregular intervals, lines that had outlived their usefulness crackled to pieces, only to leap out with the names and numbers of the arriving trains (delaying the final piece for a split-second, as if they were composed of mistakes). The stranger shared the general obliviousness. She straightened the square glasses on her face with her splayed fingers as she spoke rapidly to someone Krylov couldn’t see, who was resting his creased carry-on bag comfortably on his sneakers. It took Krylov a few minutes to realize that this someone was in fact Vasily Petrovich Anfilogov, who was not disguised in any way but who had grown a tobacco stubble, which after the couple of months of the expedition would become his usual bushy beard. Vasily Petrovich noticed Krylov as well and beckoned to him with an imperious sweep of his arm meant to reveal the flashy watch under his cuff.

They mingled greetings, and the practical Kolyan ran up, presenting Anfilogov with a fan of baggage-claim tickets. Even so, there was still a hell of a lot of baggage underfoot, so Krylov quickly loaded up, slinging the canvas straps over his shoulders and carelessly (letting anonymous hands do the passing) entrusting his light but cumbersome package to the stranger. Lanky Kolyan, smiling with wet steel teeth, slipped carefully into the straps of a backpack he personally had sewn, where the pride and joy of the expedition rested heavily: a Japanese motor purchased instead of a dentist’s services. Anfilogov tossed his raggedy cap jauntily on his head and led his small brigade through a dank tunnel occupied by a camp of Asian beggars who had come to make money and had already set out what looked like boxes of chewing gum under the scattered rain-coins (professionally sensing precisely where the roof leaked).

At last they stepped onto the platform. The train hadn’t pulled in yet, and the open expanse of rails and cables was empty, like a drawing lesson in perspective. An indefinable but amazingly precise human figure mounted the steps of the pedestrian bridge schematically drawn above the ravishing morning clouds, trying her best with her childish gait to help her baggage cart along. Kolyan, whose eyes were watering like crazy, was trying to smoke and yawn simultaneously, and smoke was pouring out his covered mouth like from a damp stove. Anfilogov, perfectly composed, profiled in the hubbub of the platform, reminded Krylov of the romantic criminal he in point of fact was.

“If you would be so kind, then, be ready to work in mid-September,” he addressed Krylov, shifting to that dry, staccato tone that had won him a bad name among easily wounded university bosses. “Buy the rest of the equipment. You can spend all the money. We’ll make up for it with interest.”

From the way Anfilogov lowered his voice, Krylov understood that what he said was not meant for the stranger, who was standing a little ways away, with gooseflesh on her bare arms, hugging the package. The woman obviously bore some connection to Anfilogov—amorous rather than familial or work-related—but Anfilogov made no effort to clarify their relationship. Krylov had still not had a proper look at her. A cursory glance had taken in vaccination scars like oat flakes, a tiny patent leather purse, and a pink, mannish ear, behind which unconscious fingers kept tucking a lock of hair cropped short. Standing close to the strange

r, Krylov for some reason lost his sense of his own height and couldn’t tell whether he was in fact taller or not. This woman seemed wholly self-contained. Meanwhile, she must have been initiated somehow into the expedition’s secret and purpose because an anemic flush spread across her cheeks, spilling under her glasses, and the general excitement, which the men hid behind their practicality and usual bravado, played inside her like a matte light.

Now Krylov was wishing Vasily Petrovich and Kolyan would just leave. He wanted to be seeing them off so that he could finally move on to awaiting their triumphant return—all the more triumphant for being so predictable—with their stash of amethyst druses to distract envious eyes. At last he heard a low, ragged whistle, and the top of the locomotive pulling its train cars came into view, getting bigger and bigger, until it filled one of the long voids of perspective. The train swooped in, its brakes hissed, and the lady conductors with their pale legs glided up in the open doors as the train slowed. While Anfilogov, Krylov, and Kolyan were hoisting the baggage into the train car, dragging it down the sun-striped corridor, periodically getting stuck, and arranging everything, taking turns on the bare brown leatherette bench in the cramped compartment, the stranger stood down below, and between the shadowy train cars a slanting sliver of sun, like a rifle with a blindingly bright bayonet, crossed her closely planted, untanned legs.

From time to time Krylov stole a peek at the woman through the dirty window mottled with the dried traces of either Chelyabinsk or Perm rain, like bird droppings. Once in a while the train shuddered and a gasping spasm rolled from its head to its distant tail, and then Krylov imagined the shadowy cars had rustled a little, like large flags touched by the wind, and the sunny sliver spilled over and, uncontainable now, streamed out. An oncoming train that had filled the little station backed off to the left, hooted, expanded, and broke away, revealing a cold expanse the size of a steel lake, humps of boulders scattered with rusty needles, and deep blue mountains to the horizon.

In fact the train was still waiting. The professor tapped his nails on the thick glass, looking out at the stranger, who ran up at his signal. Standing on tiptoe, she pressed her long, precisely delineated palm to the window. Anfilogov put his own there in response, and Krylov was amazed at how similar these hands were: there was something Latinate in their lifelines and a wonderful elegance to their finger bones. Without waiting around for any more instructions or parting words, Krylov quickly climbed down from the car. He was definitely in a bad way—doubtless the effect of a sleepless night. Everything he had seen was amazingly distinct and had left an extraordinarily sharp stamp on Krylov’s mind. No sooner had he jumped the two iron steps to the platform than the dusty train gave a shudder of relief, spilled what was left of the water in its pipes on the rails, and slowly moved off past the row of well-wishers, as if counting them off. Striding after it, picking up his pace with it, Krylov drew even with the stranger, who was waving at the windows slipping away, until finally the train’s tail popped up, like the back of a playing card.

At first it seemed an accident that they were staying even. There was only one exit—that same tunnel, where Krylov managed to shake off a nine-year-old Asian child hanging onto his companion, a wretch with lustful male eyes whose sticky paw had already nearly crept into the stranger’s defenseless bag. On the front steps of the train station, where they should have parted, since they hadn’t been introduced, Krylov suddenly felt he simply couldn’t face the solitude of the day, which was still as fresh and radiant as if the sun’s warmth had just dissolved its minty, sleepy haze but which already held nearly its fill of the heavens’ void. Running his worn shoes over the crumbling steps, Krylov ventured a joke. The woman looked around inquiringly and stumbled, pushing her glasses up. Right then on the station plaza a brass band, the likes of which had never been seen before, struck up a tune. A rotund gentleman with a cross-shaped emblem on his jacket lapel, an emblem repeated by the tasseled party standards, strode out like a pigeon before a rank of quasi-military men, whose various thicknesses and slouches made them look like pickles.

Struck dumb, Krylov, who heard only the sound of his own plugged-up brain, took the stranger’s elbow and tried to smile. The woman freed herself with a gentle shrug, and without looking at the band or the rank, set off quietly in the opposite direction, as if testing the strength of the invisible thread that connected her to Krylov. Where she was heading, everything looked brighter and better than in the other three corners of the world: a small pharmacy was bedecked with elegant, gift-wrapped medicines; a small fountain on a wet pole looked like a toy windmill, sparkling cheerfully in its watery web; and the many empty streetcars at the last stop swayed, creating their own special dimension of rocking, windows, and reflections in windows, and the passengers stood there stock-still, their eyes screwed tight by the sun. Afraid that if he didn’t start after her immediately the woman would simply unwind him, like a spool of thread, down to some naked core, Krylov hurried in her wake, and fell in step, quickly finishing his interrupted joke. A cagey smile was his reward.

“Actually, I’ve liked that joke since I was a kid, too,” said the woman archly, stepping slowly across the wobbly slabs, which squelched with the dampness of the flowing fountain.

“I know lots of others,” Krylov hastened to inform her.

“All my favorites, I bet,” the woman remarked.

“Then I’ll tell each one four times.”

“Are you always so talkative?”

“No, just when I’m hungry. Hey, have you had breakfast? Look, that cellar over there, it must be a café.”

“It’s not a café, it’s a travel shop.”

“You mean they don’t sell anything edible here?”

“They do, but it all tastes like it was made the day before yesterday. I don’t advise it.”

“That’s okay. Once I survived an entire month on canned food that was all eighteen years old. Just imagine: you open a can and instead of meat there’s a piece of dry peat. I cooked a jelly out of the cubes and paper, and it swelled up.”

It was a very odd, very long day. The whole city and May had just shed their petals, which lay like tissue paper in the warming puddles. The sweet, faint smell of decay and damp tobacco mingled dolefully with the bold green smells of the fully opened leaves, which were cold to the touch. For a long time each one felt that the other was leading the way; each was merely following the stranger’s whim. At the slightest misstep, afraid of getting separated, they concentrated on finding their line of equilibrium, which sometimes led them right into the street. They were looking out for each other’s movements; sometimes their arms bumped, and then each felt as if they had accidentally touched a bird in flight.

Probably only from a great height—where a small advertising blimp hovered, dusty in the sunny thickness of the air—could you begin to understand and read the tentative curve their movement described through the city. But they didn’t understand anything. They just kept turning up in places, often unfamiliar ones. They found themselves at an outdoor marionette show, where marionettes in pretend shoes that looked like bread crusts looked as if they were trying to break free from the strings of their stooping master; the very few spectators were absorbed not so much in the content of the play as the progress of that struggle. They were drawn through a small political rally, which filled the neighborhood with marching verses. Led more and more downhill, they gradually approached the city’s river with its park pond, deep as a belly, where all the things that fell into the river, including drowning victims, accumulated and stewed. Here, below, they roamed cross-country—over fresh ditches with stone abrasions and old gray slopes sparkling and slippery from broken glass. Here they couldn’t keep moving identically as before, so they demagnetized. Each scrambled separately—and the stranger, skidding comically on her heel, slid down the pitch straight into his clumsy male embrace. Krylov immediately let go of her slippery ribs, but he had felt the round heft of a jumping hemisphere and beneath it,

like in a pocket, a trembling heart the size of a baby mouse.

Later, faced (fated?) with this experiment on himself, Krylov tried to figure out what had actually held him back at that fateful train station plaza. After all, it would have been easy to separate, and as evening fell he would have recalled their chance meeting over a beer at his workshop, enjoying the bliss of the semi-dark, which was like a caressing fur after the harsh light of work. However, instead of going and working on his important order, Krylov, like a high school senior, played hooky with a faded beauty who raised a ticklish draft in him.

The reason probably lay in the special excitement, the alteration of his destiny that awaited Krylov in the event of the expedition’s success. What did he care about the agate cabochons, the assortment of rejected stones fit for the street vendors? For months he had lived with an incomprehensible hunger. Night after night Krylov’s bed was sprinkled with crumbs, like the sands of a desert spread out around him. In short, in his daily rut a hole had formed that he had to fill. At night, Krylov dreamed of big money—the kind of money that would last far beyond his lifetime, settling its possessor in a comfortable eternity. But he ended up getting something very different from life. How the substitution came about, Krylov and the woman simply could not understand.

That day, after setting off on foot from the station, they wandered through the streets like tourists. Hunger and anonymity imparted a special ease to their shared, increasingly coordinated gait, and they got better and better at staying together. In an open-air café in the park, where Krylov and his companion stopped for a bite to eat, a faded Sunday menu lay on the little red formica tables, although the calendar said it was definitely Wednesday. In the lazy park, though, it was always Sunday, and across the pond, swathed in an oily light, a dingy white swan glided in its own wave, as if on a plate; at the shooting gallery shots clicked; and on the woman’s neck a spot of sun, flickering, fastened itself to her vein, like an improbable cartoon vampire. Relaxed in the pale sun, which had warmed the wobbly formica a little, the stranger informed him, at last, that her name was “Tanya, let’s say.” It wasn’t her real name; he could tell from the slight hitch in her confident voice. Joining in the game, Krylov introduced himself as “Ivan,” to which the freshly named “Tanya” chuckled delicately, taking a sip from her plastic cup of synthetic juice.

2017

2017