- Home

- Olga Slavnikova

2017 Page 6

2017 Read online

Page 6

They did not save the day. Everything changed. Nothing seemed real anymore but rather as if you were seeing it in a mirror in which you couldn’t tell who was doing what or who was going where. Young Krylov still didn’t have the right words but he did have a visceral sense of the disorientation of things; he noticed that many people on the street now seemed off. Others, who didn’t speak Russian well, seemed to double in this mirror: in the courtyard, each time he ran into mocking Mahomet with his iron fingers, or Kerim with the blue-gray head from the seventh floor, young Krylov felt with his drawn-together shoulder blades that, while they were in front of him, they were simultaneously behind him. In the evenings, they turned off their electricity; everyone sat in the kitchen around the one candle, which melted as it burned into a warm puddle; in his book, which he managed to fit among the dirty dishes, black pictures stirred on yellow pages. His father, wiping his teacup with a greasy crust of bread, would tell the story for the umpteenth time about the man from his institution who had made certain “improper attacks” against him and cut him off on the street for no reason at all.

Strangers came to the Krylovs’ apartment: two who looked liked they were from the market, wearing identical jackets that looked like they had been glued over a piece of warped cardboard. The strangers walked through the house, looking around cautiously and meticulously. One, with temples like pieces of gray coal under his skull-cap, asked Krylov’s frightened mother something, his angry, effeminate voice rising from time to time to a quizzical whine; the other said nothing but seemed to be thinking, and the wrinkles on his forehead were exactly like the ones you get on the front of crumpled trousers. One day these two, whom his parents referred to privately as “the buyers,” brought with them an utterly senile and bent old granddad whose body looked like a skinny dog in man’s clothing. While the young men were crawling under the bed and in the closets—now without any ceremony whatsoever—the granddad sat on a stool, his bowed legs in their soft, dusty shoes folded in an impotent curl. Granddad looked absolutely nothing like the rich merchant whom young Krylov’s imagination had created with a little help from the Arabian Nights. His robe, belted with a dirty cotton scarf, had been incinerated by the heat to shreds of brown batting, and his beard was like the threads from a torn-off button. When young Krylov happened to look into his eyes, where some kind of warm wax was accumulating, he felt—as clearly as if he had become transparent for a second—that this granddad didn’t care what happened to him, or to these young men, or to the Russian inhabitants of this profane apartment, who to this granddad were no more than shadows on the unfamiliar walls around him. When they had completed this latest inspection, the strangers lifted the doddering djinni by his spread elbows and walked him off, adjusting to his small felt steps—and from the vestibule you could see the Permyakovs’ door open across the landing and the anxious neighbors waiting inside. There were fewer “buyers” than “sellers.”

The “move” dated from this time. By no means all the familiar items that disappeared here showed up later there, in the cold northern city where the trees’ summer greenery functioned as a raincoat, in the tiny apartment stingily lit by windows the size of an open newspaper. In the same manner his aunt disappeared as well—the princess, his friend, the beauty with the round face that glowed in the dark—she vanished without a trace, and young Krylov understood from the muffled tone of the new apartment silence that in no instance was he to ask about her. It turned out that the precious stones were all gone, along with Mama’s savings, to pay for the containers in which their furniture arrived, crippled and suffering from, now chronic, dislocation of the joints. The wardrobe where his aunt’s colorful dresses once hung now had a tendency to come apart, the way the slick magician’s painted box comes apart in the circus ring.

An adult might call the emotion young Krylov experienced disenchantment. In fact, it was a mixed sensation, like acute orphanhood while your parents are still alive. He recalled the morning of their departure, when the air was like chicken broth. The boys whistled for him to come outside, but he was in a new part-woolen suit, which made the grass and old roses by the front door seem part-woolen, too. He remembered both the reserved seats on the train, which was permeated throughout with the sadness of the long sunset lying low over the steppe, and the unfamiliar taste of crooked green apples bought at the station—a taste like cotton wool and medicine from the pharmacy. At the same time, he didn’t think he would remember anything. Life split between “before” and “after.” For a long time young Krylov couldn’t get used to the idea that the summer here was so inauthentic, like the reheated leftovers of the previous year, when he had not yet been in this apartment or this yard, where no one ran around barefoot.

No matter how hard his parents tried to get it out of him why he had done that terrible thing, young Krylov preferred to keep his own counsel. You didn’t see him asking why they hid the only photograph of his aunt as far away as possible, under the technical manuals from the nonexistent microwave and sewing machine, although he suspected foul play—a reluctance to look at the person they had for some reason abandoned. One evening, scarily close to his parents’ return from work, he decided to poke around in the stiff drawer under the mirror, which was crammed full. Hastily tossing the uninteresting papers aside, afraid now that what he’d been searching for would not turn up among these scraps, he suddenly saw his aunt—taken in the same studio where they had taken him, standing as if she were a singer on stage, in front of folded drapery which young Krylov remembered as red but in the photo was brown. All at once his urge to steal from his parents the sole copy, which had no original, was superseded by another. Feeling the tears that had welled up press on his nose, Krylov ripped the photograph into sticky pieces, some of which ended up on the floor. Then he managed to unseal the damp ventilation pane and released his aunt from his fist, like a small bird, onto the dark October wind that was scraping its belly over the earth, trying to overcome the mass of air and withered leaves pulling it down and fly south. He didn’t notice that some of the scraps fluttered back into the room and got tangled in his hair like confetti.

When his parents, tired from the bus, dragged themselves and their bags of groceries into the utterly quiet, unlit apartment with the electric drizzle on the uncurtained windows and the little criminal hiding in the dark toilet, all the clues were in evidence. Young Krylov couldn’t remember another fatherly punishment like this one: the belt seared his clenched, trembling buttocks, and the pain made him wet himself on the clammy oilcloth his father had thrown down as a precaution on the new ottoman brought from the house. His mother, clutching her crushed beauty parlor hairdo, sat at the empty table in front of a solitary dish of marmalade and the remnants of some colored sugar—and remained sitting like that while the criminal, holding his trousers and upturning chairs, stumbled back to the toilet, where he kept tattered matches and smelly butts wrapped in paper behind the wastebasket.

Actually, what shook young Krylov at the time was not his parents’ behavior but his newly discovered capacity to commit terrible crimes. He developed this capacity further in school and the yard, which was notorious for its drunken brawls, teen rumbles, and the giant puddle, shaped like a grand piano, that appeared spring and fall in an unvarying outline in the exact same spot. After the “move,” young Krylov got out of hand, as they say. A ceasefire was in effect only on museum territory, where, if his mother didn’t pester him too much, Krylov quietly did his homework in the staff room with the thick walls and sloping window, where the raspberry sun of the winter sunset sat like a loaf of bread in the oven, or the spring branches melted in the March blue. All the rest of the time he led an independent life.

Unlike the children of all his parents’ old friends who had moved from Central Asia to cold Russia, Krylov was almost never ill in his new homeland. Never was he hit by the deep frosts, which transformed the industrial city into a dim, enchanted garden, or by the famous Riphean snow showers—cold oatmeal on water, w

hich tasted of coal; in the fickle northern sun he tanned to an Asiatic blackness. In everything that had to do with health, the teen Krylov was the utter despair of his parents and at their slightest attempt to instruct he would storm out of the house before he could tie his army boots, the only ones he had, stolen at the wholesale market.

He and his thrill-seeking buddies would ride the freights that dragged past the long row of gray buildings, or he’d flatten pieces of scrap metal under train wheels, scrap that seemed to retain some of its terrible weight and quaking power, like the echo of the caboose, as if the freight train, making its groaning sounds, were retreating from him in both directions. With that same enterprising gang, young Krylov climbed the abandoned TV tower the Ripheans called the Toadstool. The town’s main attraction, it had never been used for its original purpose and for a good ten years had been deteriorating in a striated mirage above the cubist apartment blocs and cellophane river, guarded by the police, but only very theoretically. There, inside the concrete pillar, which had holes like a whistle, the rusted stairs were rickety and some places were like a creaking swing. The wind up top, bursting through the cracks, instantly dried your sweat, making the thrill-seeker feel as if his whole body had been trapped in a sticky spider web. Despite the difficulties of the climb, though, the column was covered in graffiti just as solidly as any proletarian stairwell. At the very top, on the wind-lashed circular platform, which bobbed around like an airborne raft, he couldn’t keep his feet at first, even in the relatively safe center; he felt like lying flat on his belly and not watching the skinny grating of the guard rail, buried by winding tendrils, ladle the sun-drenched blur, not watching the pink rag that was tied to it and ripped to shreds flap furiously.

Teen Krylov had already figured it out, though. If you wanted to be a real Riphean, you had to take risks—lots of them, and the more reckless the better. Standing at the very edge, feeling where the low wall stopped and emptiness began, just above knee height, like a cello bow passing across strung nerves, he was one of the few who could piss straight into the abyss, where his output scattered like beads from a broken necklace. When out-of-town base jumpers first showed up at the tower and started jumping over the side, flicking the long tongues of their parachutes like lighters, Krylov decided he was definitely going to jump, too, but it was not to be.

“Don’t even think about it, buddy,” a guy with kind, deeply set eyes that glistened amid his wrinkles and lashes like drops of dark oil told him. “You have to train for six months to base-jump. It comes down to a matter of seconds, get it? You could fuck yourself up good.” The good man explained what exactly would happen to Krylov, using an expression of exceptional profanity while looking good-naturedly around the thrill-seekers’ hangout, where an empty balloon drifted, drunk on the thin air and shining like a sixty-watt bulb in absolute sun.

“So I fuck myself up. So what? It’s my right.” Krylov wouldn’t back down.

“See this parachute?” the good baser nodded over his shoulder. “It costs two grand. If you fuck yourself up, I’m not getting it back.”

This argument convinced Krylov. The two grand figure made an impression. Krylov’s activities outside the house now tended to be partly commercial in nature. He and his buddies, wearing loose Chinese-made Adidas sweats, shoplifted on a small scale from “their” supermarket, the Oriental, keeping cheeky outsiders off their territory. They prospected at Matrosov Square, formerly Haymarket, where the river lay on the sand like a woman on a sheet, and under the sand, in the black, foul-smelling muck that used to be cleaned off the bottom by the municipal cleaners, they’d find different coins, gold ones even, as small as a Soviet kopek, with a two-headed eagle the size of a gnat. Soon teen Krylov’s mind had invented a kind of virtual bookkeeping. A parachute was two grand. A used PC—two hundred fifty. The new World Coins catalog—fifty-four. A headlamp for crawling through the vaulted shallow underground mines—eight hundred rubles. A sturdy Polish backpack—four hundred fifty. Not all—or even many—of his dreams could come true.

Teen Krylov adjusted to jumping from the Toadstool in his dreams. As he drifted off, his URL was a specific array of sensations—in particular, the image of a balloon being borne off, which tuned every nerve in his body to the four hundred meters of altitude, at which point the balloon reminded him of an astronaut stepping out for a space-walk. Not always, but often Krylov reached a state where everything was swaying, tossing, and whistling. As in real life the clouds’ wet shadows floated deep in the golden abyss and were greedily collected by the city blocks, the way water collects pieces of sugar. In his dreams, Krylov broke away from the concrete by making a special effort with his tensed diaphragm; immediately, his ears and head felt like a jammed receiver. The paradisiacal two thousand-dollar parachute on his back just wouldn’t open, so he had to dissolve in the wind as fast as possible and without a trace, which Krylov set about doing quite practically, surrendering utterly to the logic of his dream and its vibrating, vanishing words.

When he started earning some money, teen Krylov felt more grown up than he really was. He’d been through all the trivial agonies of a self-centered young oaf with a laughable father (by this time his father had become a toadying chauffeur for a piss-ugly boss and was driving a Mercedes, just like he’d always wanted), and things got much easier for him with his parents. His silence in response to their helpless cries now seemed perfectly natural, and from time to time he would even leave his school report in the kitchen, by way of impersonal information, a perfectly proper school report with good marks. Studying came easily to Krylov. What was worse was that his parents’ mere presence kept Krylov from having a good read. They obviously suspected him of hiding a porno magazine under his algebra textbook—not a Frederic Paul novel.

All in all, relations between teen Krylov and his parents consisted of endless suspicions. Imagining what they were imagining while they waited up for their sonny boy at night under their stupid kitchen lamp, Krylov admitted that no matter how hard he tried he could never be as bad as that pair who had once conspired to give birth to him thought he was. Looking at them, Krylov could more readily have believed that he’d been conceived in a test tube. He was perfectly well informed about where children came from, and he had enjoyed the favors of Ritka and Svetka, two sisters one year apart who never said no and who had rough kissers and soft asses. Krylov could not possibly imagine his mother and father getting it together to have him; and he really couldn’t understand why they’d bothered. Krylov’s parents flattered him with their fears. No matter what happened in nearby neighborhoods—a fire at a kiosk that had stood there ever since in the form of a hut of black and fresh plywood, a burglary at the apartment of the hereditary dental technician who had kept the secret of his family collections all his conscious life and was now forced to keep it, except as someone else’s—in everything they saw the complicity of their son, who had no alibi. Their delusion was so strong that his father, who considered himself something of a diplomat, even attempted to win over the dental technician, who had parked his secondhand Zhiguli next to the Mercedes, but the technician, who had the skull of an elephant, not a man’s, on his short body, reacted like a rape victim and clarified nothing.

In short, his parents believed that Krylov was to blame for every crime committed in the vicinity. The image created by his parents’ imagination coincided with Ritka and Svetka’s ideal—someone to share, like all their boyfriends and their cheap dresses with the gold sparkles and puff paint designs. They pictured this ideal as a tough guy who thought life meant having control over everything that moved and who was on friendly terms with a benign papa-thug, whose thick shaved neck sported a gold chain as chunky as a tractor tire. All the gang—from the lookout with the shaved head, whom Krylov had only seen from behind, to puny Genchik, famous for his ability to send his bubbly spit flying several meters—possessed a common quality: a nauseating soulfulness. They took serious offense if something seemed amiss to them. Some fuzzy-eyed mor

on with a head no more complexly constructed than a gearbox could for some reason remember a guy and chase him down like a jackrabbit, becoming the ubiquitous godling of their home courtyards and garages as far as his victim was concerned.

These tattooed punks horsed around for a long time before installing their own general at the Oriental—Krylov’s classmate, Lyokha Terentiev, who’d repeated two grades. Lyokha’s close-set eyes studied intimidation and practiced on the other guys, provoking a rush of malicious energy in Krylov and an urge to crush not only Lyokha but the store he’d taken over as well. Actually, Lyokha himself, being both curious and clumsy, had overturned a rack of housewares, and the crash buried the unfamiliar object that had caught his eye under a heap of enameled cookware and detergents gurgling in plastic squeeze bottles. Ever since, the general, rather than working personally, had just shot the breeze with the guard while the guys, shielding each other from the surveillance camera, lifted expensive compacts and perfumes.

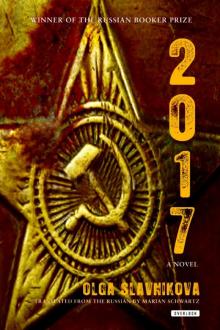

2017

2017